"Tawonga will shine tonight,

Tawonga will shine.

Tawonga will shine tonight

all down the line . . . "

Camp Tawonga Song, 1930s

Chapter One

Origins

The Early Years

The Beginning

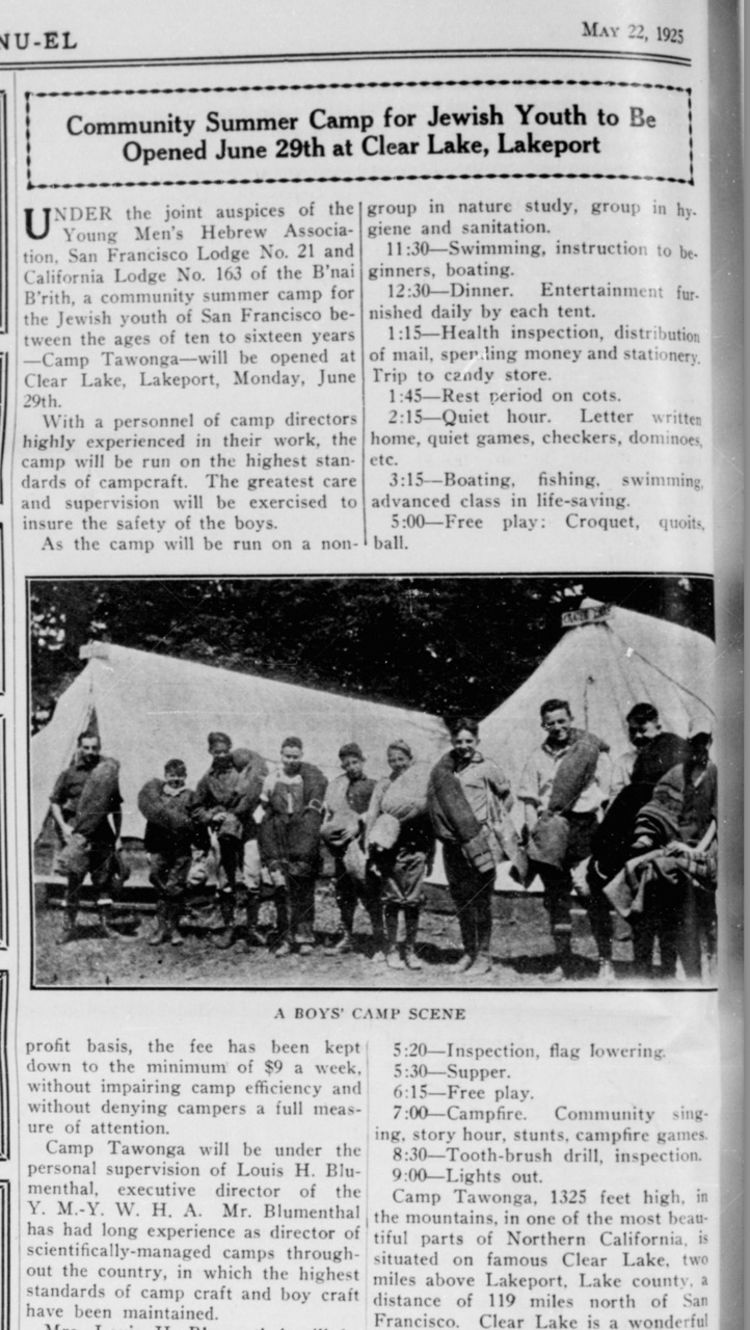

Camp Tawonga was founded in 1925 by leaders of the San Francisco Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA), along with financial support from two local B’nai B’rith lodges. It offered boys the chance to escape the city, breathe mountain air, and build strength in the outdoors while connecting to Jewish life. Girls joined the following year in a separate session — a practice that continued until Tawonga became co-ed in the 1960s.

Tawonga was founded on principles that have guided its century-long history: fostering self-esteem, promoting cooperation, respecting nature, and celebrating Jewish identity. While these goals were not formally articulated in a mission statement until the late 20th century, they were integral to its founders' vision from the very beginning.

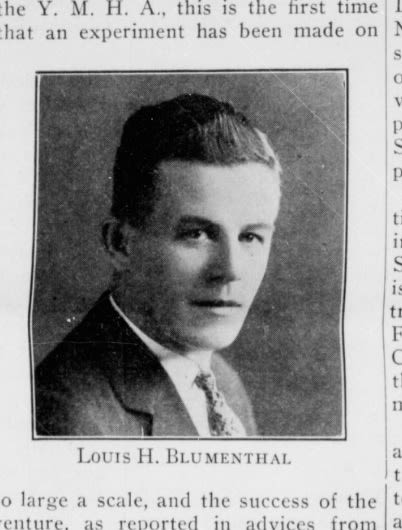

Founders

Early leadership came from prominent figures in San Francisco Jewish life. Louis H. Blumenthal, the YMHA’s executive director, became Tawonga’s first camp director, while Harold Zellerbach, a rising civic leader from one of the city’s most philanthropic families, chaired the camp committee.

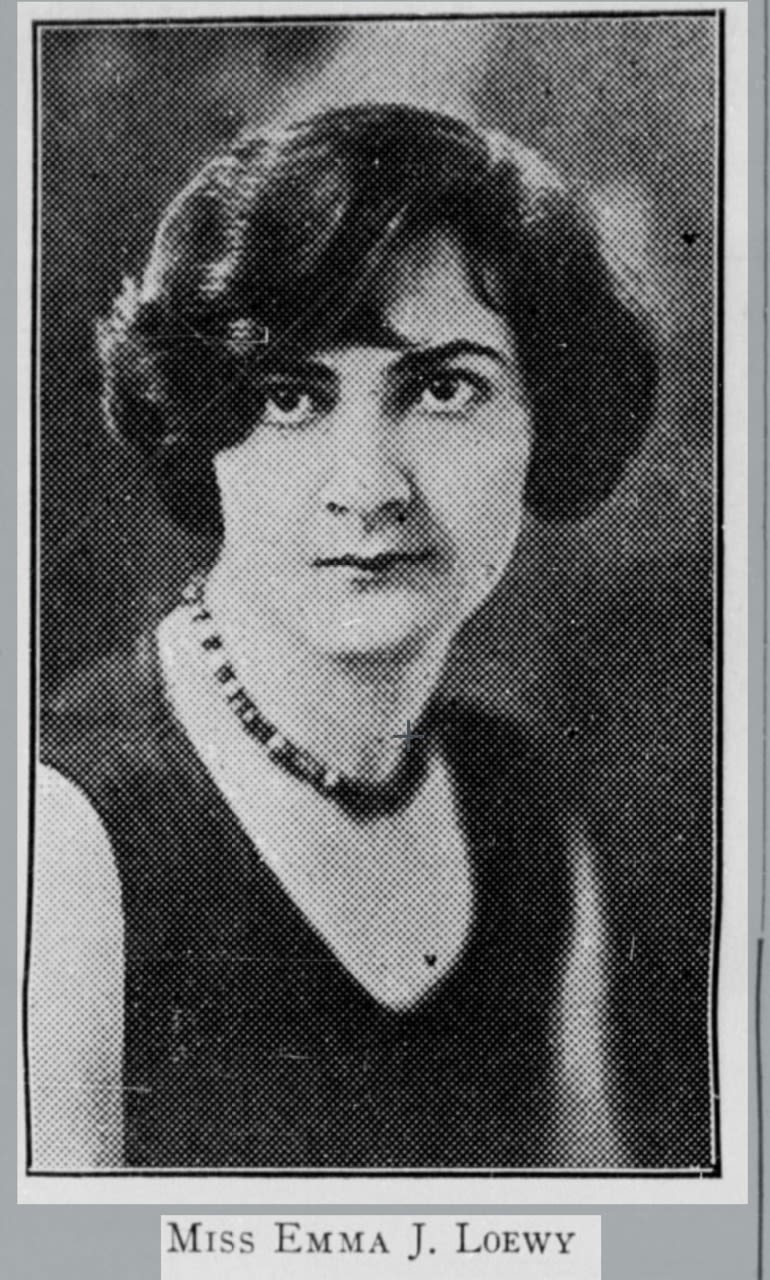

Emma Loewy, an administrator at the YMHA, became director of the girls’ camp in 1928.

Louis Blumenthal directed the camp until 1929. He briefly left the Bay Area before returning in 1933 to head the San Francisco Jewish Community Center, serving as its executive director until his death in 1959. He remained a vigorous supporter of the American camping movement throughout his life and, in 1937, published a monograph titled "Group Work in Camping."

Louis Blumenthal directed the camp until 1929. He briefly left the Bay Area before returning in 1933 to head the San Francisco Jewish Community Center, serving as its executive director until his death in 1959. He remained a vigorous supporter of the American camping movement throughout his life and, in 1937, published a monograph titled "Group Work in Camping."

Harold Zellerbach (right) visiting camp in Cisco, Calif., in 1929. Zellerbach was the grandson of Anthony Zellerbach, a Bavarian immigrant who came to San Francisco during the gold rush and eventually began a San Francisco paper company, later known as the Crown Zellerbach Corporation. Many prominent buildings and institutions, including UC Berkeley's Zellerbach Auditorium, honor the family's philanthropic legacy.

Harold Zellerbach (right) visiting camp in Cisco, Calif., in 1929. Zellerbach was the grandson of Anthony Zellerbach, a Bavarian immigrant who came to San Francisco during the gold rush and eventually began a San Francisco paper company, later known as the Crown Zellerbach Corporation. Many prominent buildings and institutions, including UC Berkeley's Zellerbach Auditorium, honor the family's philanthropic legacy.

Emma Loewy, an administrator at the San Francisco Young Women's Hebrew Association, became director of the girls’ camp in 1928 and remained in that role into the 1940s. Emma Loewy and Louis Blumenthal married in the early 1930s.

Emma Loewy, an administrator at the San Francisco Young Women's Hebrew Association, became director of the girls’ camp in 1928 and remained in that role into the 1940s. Emma Loewy and Louis Blumenthal married in the early 1930s.

The American Camping Movement

Tawonga’s founding was part of a much larger story. The American camping movement of the early 20th century grew out of Progressive Era reform. Reformers believed that crowded, industrial cities threatened children’s health, morals, and character. Summer camps, often set in woodlands or along lakeshores, promised an antidote: fresh air, physical vigor, and a carefully structured immersion in nature.

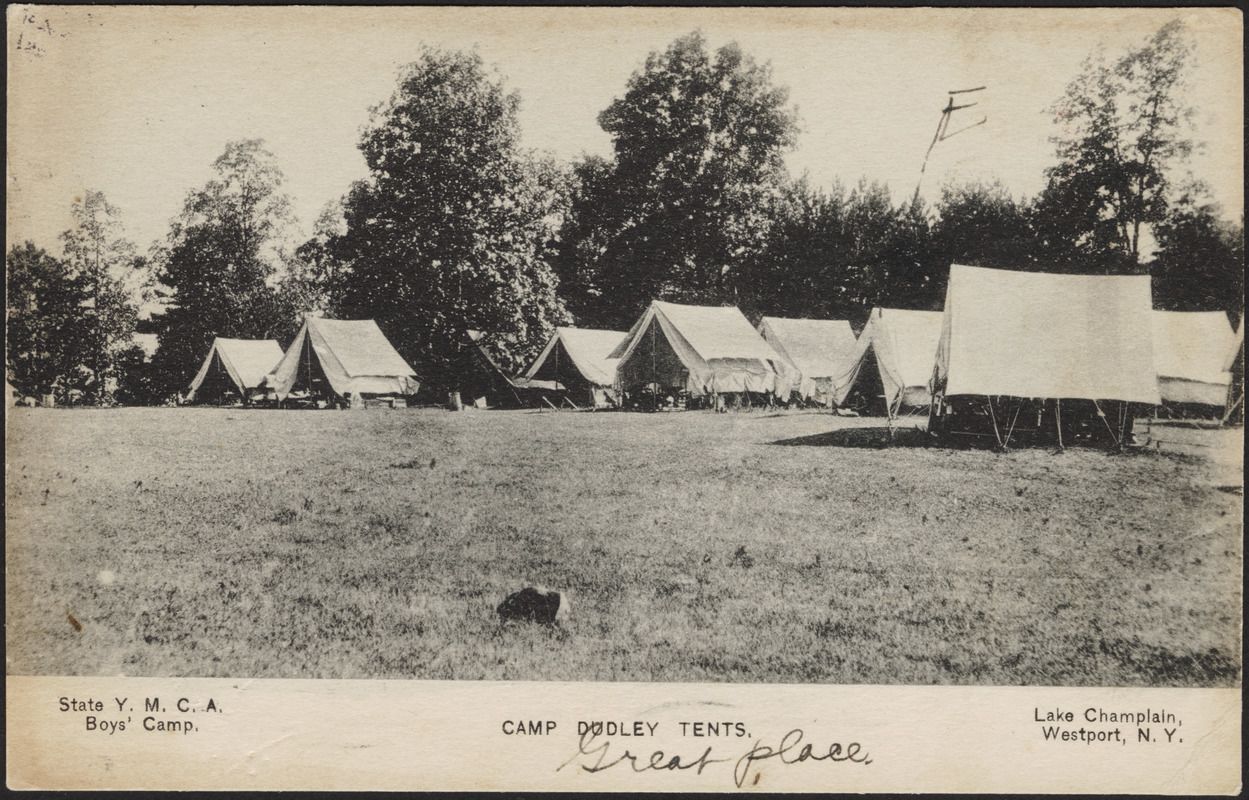

Camp Dudley (Westport, N.Y.), one of the earliest YMCA summer camps, in an undated photograph

Camp Dudley (Westport, N.Y.), one of the earliest YMCA summer camps, in an undated photograph

For middle-class families, camp was a way to cultivate wholesome habits and build resilience in boys who were thought to be growing soft in an urban age. At the same time, camps became tools of social engineering. Progressive reformers used them as laboratories of so-called Americanization, seeking to instill values of nationalism in the children of immigrants and ethnic minorities.

Lowering the flag at Camp Tawonga, ca. 1927. Like all early American summer camps, Tawonga emphasized patriotism and citizenship throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Lowering the flag at Camp Tawonga, ca. 1927. Like all early American summer camps, Tawonga emphasized patriotism and citizenship throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

The rise of organized camping also reflected broader cultural currents: fascination with nature study and conservation, anxieties about masculinity, and new ideas about child development emerging from psychology and education. Drawing inspiration from the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA), scouting, settlement houses, and the back-to-nature enthusiasms of the day, camping combined recreation with moral uplift.

The Boy Scouts of America helped shape and popularize the American camping movement in the early decades of the 20th century.

The Boy Scouts of America helped shape and popularize the American camping movement in the early decades of the 20th century.

Jewish Summer Camps

Within this national landscape, Jewish summer camps emerged as a distinctive feature. They shared the Progressive commitment to health, character, and outdoor life, while also creating space to strengthen Jewish identity, build community, and respond to the challenges of assimilation in America.

The earliest Jewish camps often drew children from working-class immigrant communities in cities such as New York and Cincinnati. Many infused their programs with Yiddish culture, Zionist ideals, or socialist values, reflecting the vibrant Jewish life of those urban centers.

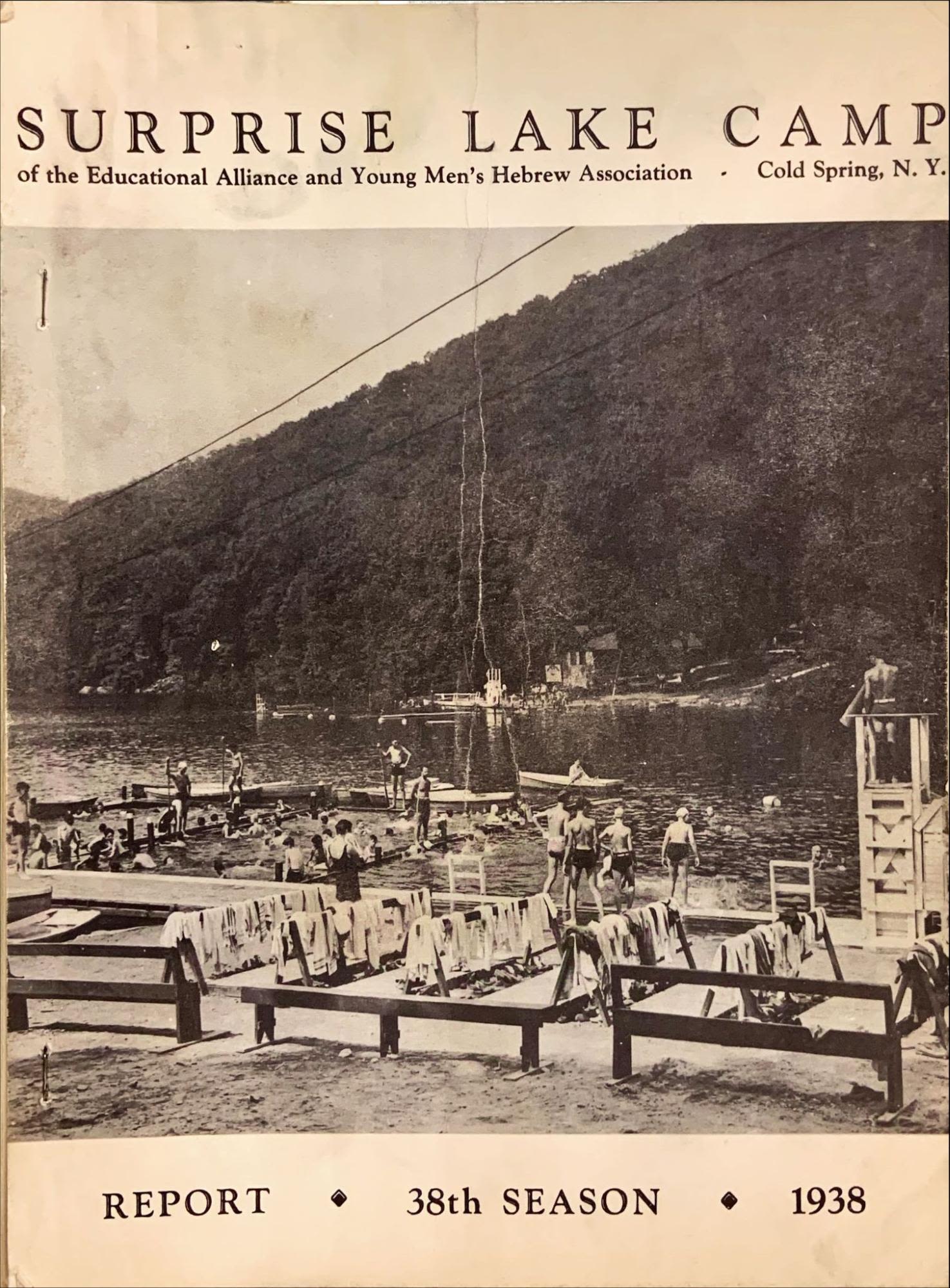

Surprise Lake Camp (Cold Spring, N.Y.) campers, ca. 1930

Surprise Lake Camp (Cold Spring, N.Y.) campers, ca. 1930

Tawonga’s Distinct Beginnings

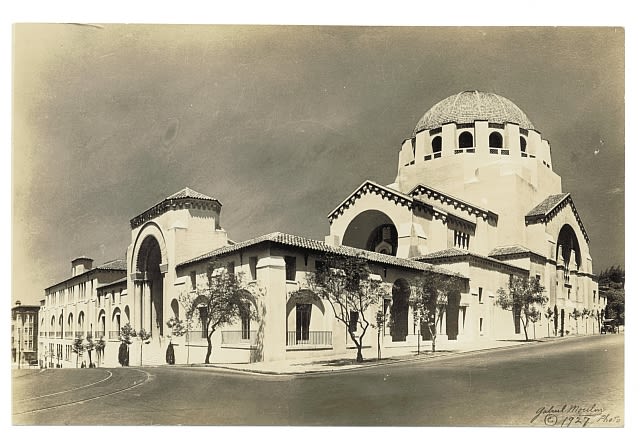

Tawonga's early leaders were mostly members of San Francisco's culturally assimilated German Jewish community. By the 1920s, San Francisco’s leading Jewish families had already established themselves within the city’s civic and business elite — a prominence symbolized by the new Temple Emanu-El building, which laid its cornerstone in the same year the YMHA opened Tawonga.

Temple Emanu-El, on the corner of Lake and Arguello Streets in San Francisco. The cornerstone was laid in 1925 and the building was consecrated and opened in 1926.

Temple Emanu-El, on the corner of Lake and Arguello Streets in San Francisco. The cornerstone was laid in 1925 and the building was consecrated and opened in 1926.

This background influenced the community’s vision for Tawonga. Unlike camps in New York or Ohio that highlighted Yiddish culture or working-class solidarity, Tawonga aimed to be a rugged yet modern camp situated in the tradition of American Reform Judaism, where Jewish children could flourish outdoors while seamlessly integrating into mainstream American life.

At the same time, Tawonga's leaders worked to ensure that access was not limited to the well-off. From its earliest years, Tawonga offered scholarships (known today as "camperships"), so that families who could not otherwise afford camp could take part. The YMHA's minutes make frequent reference to these fundraising efforts, underscoring a commitment to include young people from across the Jewish community.

Jewish Practice at Tawonga

As it is today, Jewish ritual was built into the weekly structure of camp life.

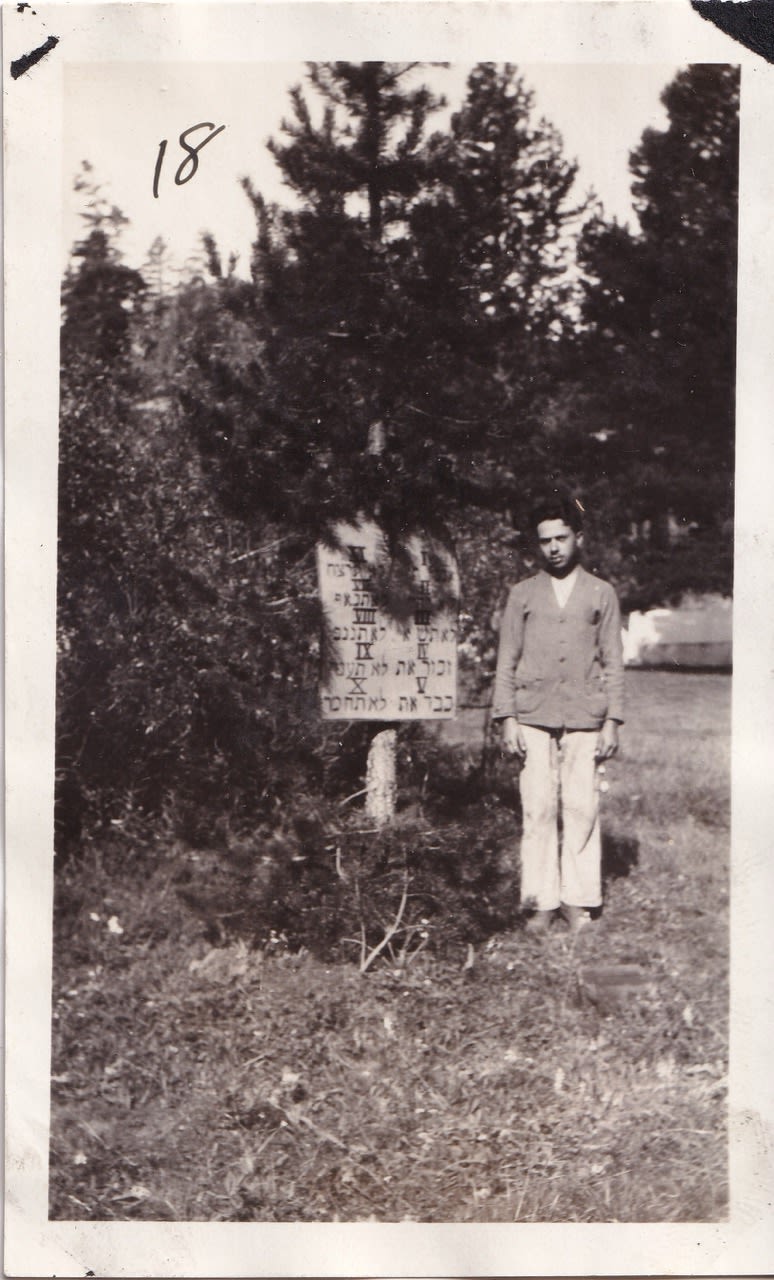

A number of photographs document Shabbat services in the woods, showing that campers in the 1920s gathered and prayed outdoors just as contemporary Tawongans do at our Tuolumne property.

One striking image shows a boy standing before a hand-painted Hebrew sign bearing the Ten Commandments — a reminder that, even in these early years, Jewish identity was woven into the fabric of camp life.

A Tawonga camper (possibly David Greenberg) stands in front of the Ten Commandments, ca. 1927

A Tawonga camper (possibly David Greenberg) stands in front of the Ten Commandments, ca. 1927

Beyond the weekly services, Jewish religious education was relatively understated in the early decades. Daily camp schedules (printed in the newspaper for curious parents) listed Jewish History as an optional block of study, but this topic was just one of many options listed at the same time, including blocks in Nature Study and Hygiene.

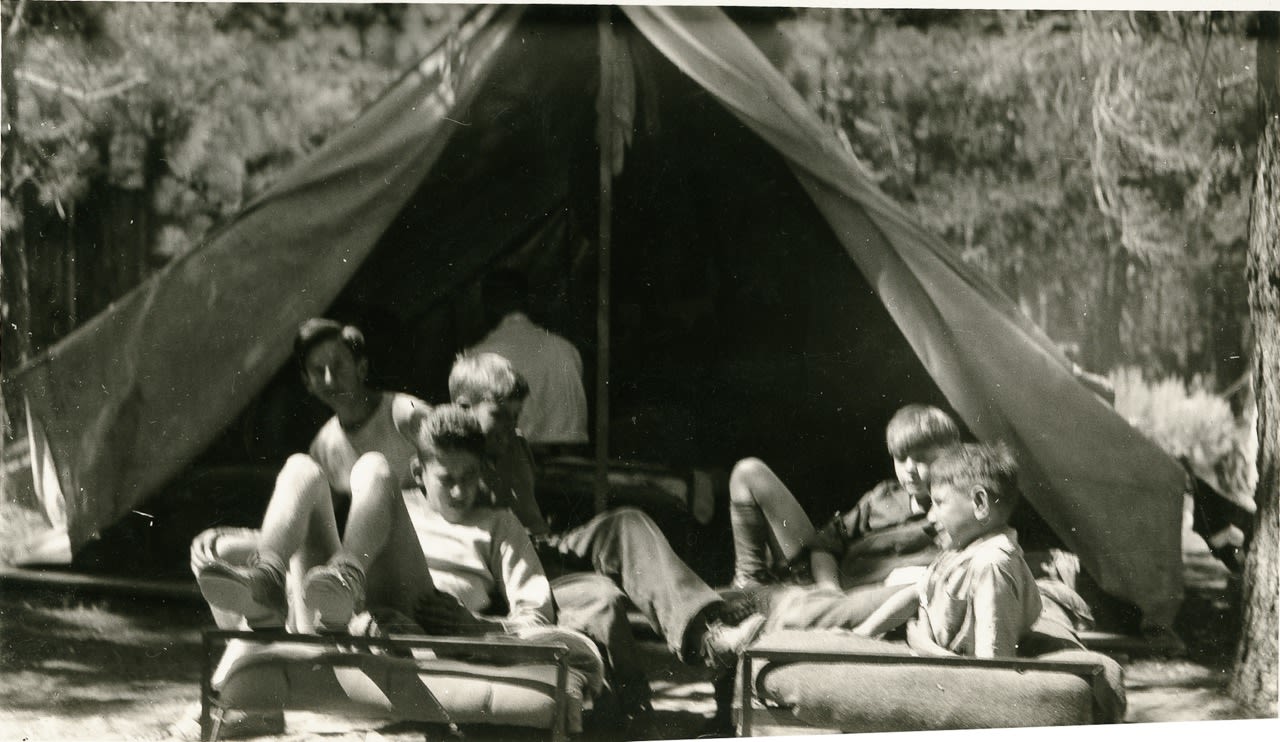

Life at Camp Tawonga

In its early years, Camp Tawonga emphasized what leaders called “vigorous living.” Daily routines focused on hygiene, health, and stamina — especially for boys. Activities included sports that were considered masculine, such as boxing, alongside instruction in traditional camping and survival skills.

"Activities include athletics, study of Jewish history, development of physical, mental and moral strength in the boy, and the inculcating of high principles of manhood and citizenship."

Life at Tawonga also carried a strong sense of responsibility. Boys were assigned chores that kept the camp running smoothly: chopping wood, hauling water, washing dishes, peeling potatoes, even scrubbing laundry by hand. These tasks were framed as part of the program, teaching both cooperation and self-reliance. To Tawonga’s leaders, the work of maintaining camp was as formative as athletics or outdoor adventures.

Tawonga campers washing clothes, ca. 1928

Tawonga campers washing clothes, ca. 1928

Tawonga campers doing morning calisthenics in 1929

Tawonga campers doing morning calisthenics in 1929

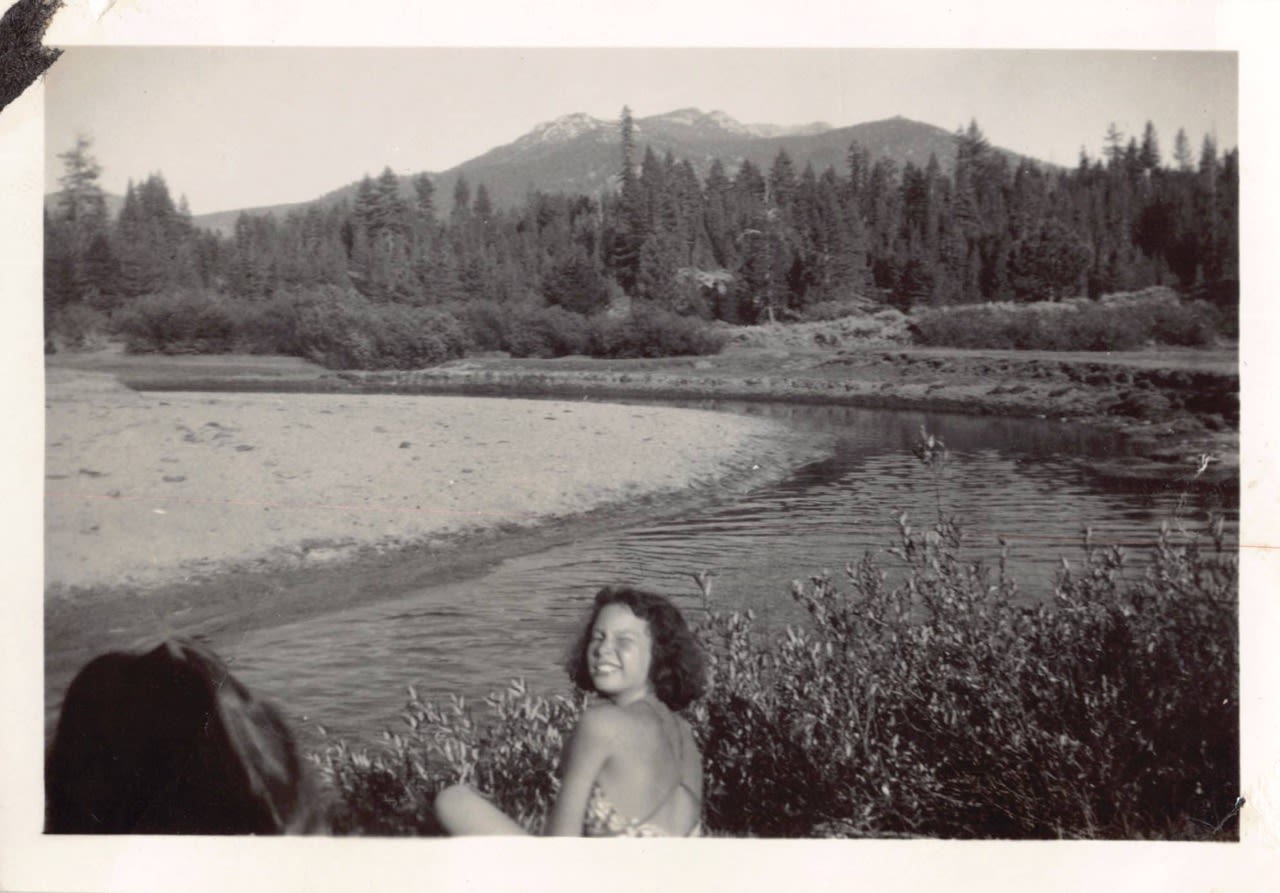

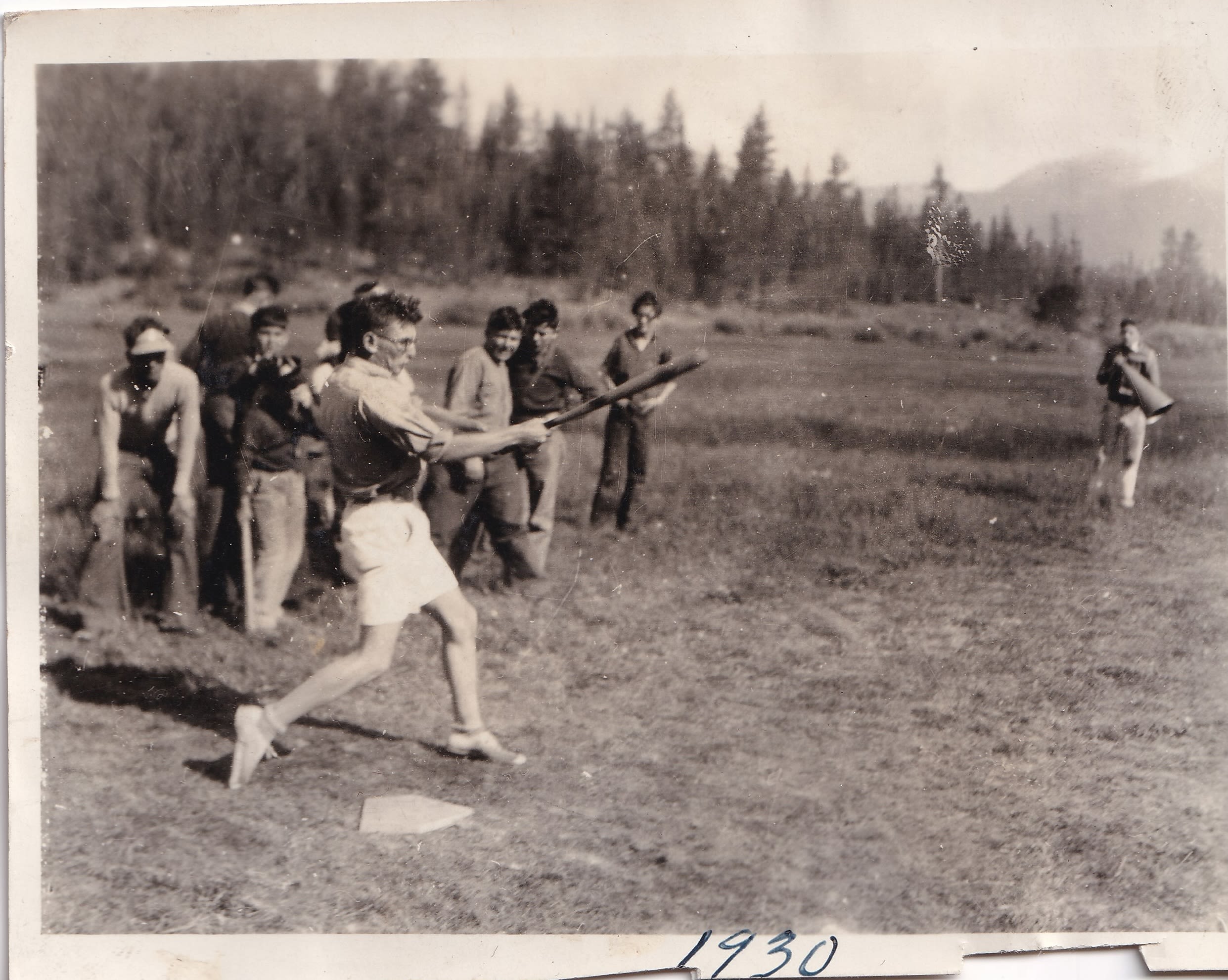

Despite the chores, there was still plenty of time in the day for fun. Photos from the time show Tawongans swimming in creeks, playing baseball, dressing up for performances, setting off for hikes, and even riding horses. And, of course, there were plenty of campfires with songs, stories, and traditions.

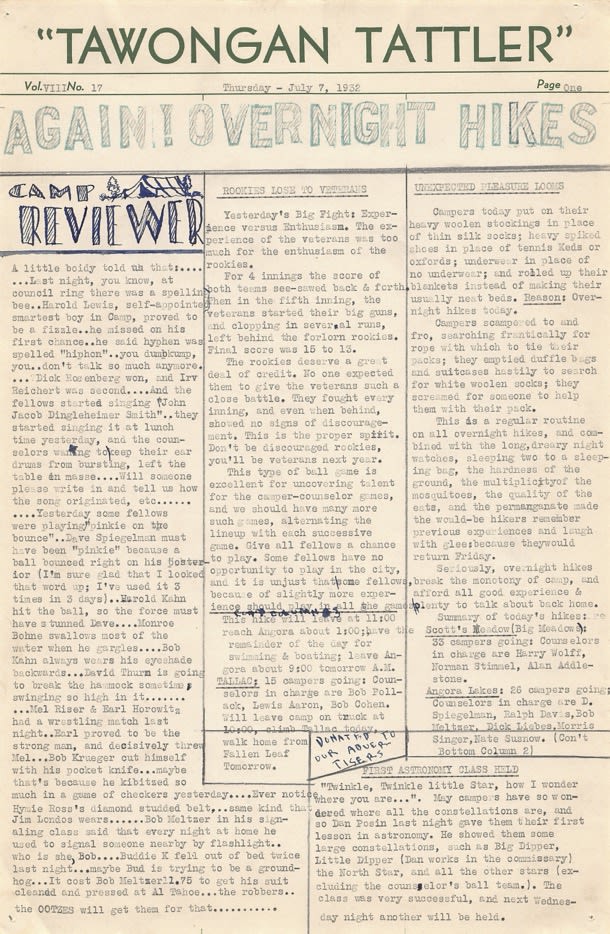

In the 1920s and 1930s, campers at Tawonga also produced a regular typewritten and hand-illustrated newspaper, the Tawongan Tattler. The paper reported on life at camp, its pages full of (now entirely cryptic) in-jokes and nicknames.

Tawongan Tattler from July, 1932

Tawongan Tattler from July, 1932

Girls at Tawonga

Girls arrived at Tawonga for the first time in 1926, in the camp's second year. Across the country, overnight camping for girls was still relatively new, growing alongside organizations such as the Camp Fire Girls (formallly established in 1912) and the Girl Scouts of America (1910). These movements reflected a Progressive Era conviction that girls, too, could benefit from time in nature — though their programs often stressed cooperation and character more than rugged survival or competitive sport.

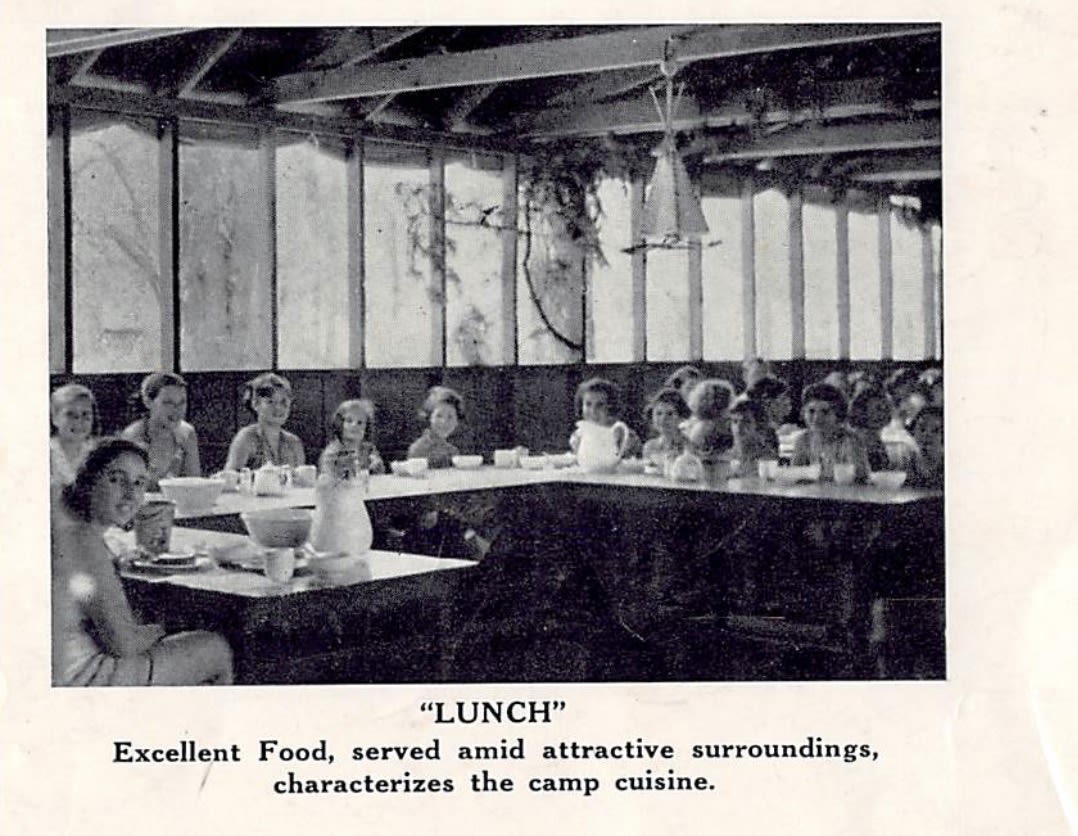

At Tawonga, girls took part in many of the same activities as boys, but their programming often reflected cultural expectations about femininity. Under the leadership of Emma Loewy, who directed the girls’ camp from 1928 into the 1940s, children participated in arts and crafts, music, and decorative projects, alongside lessons in teamwork and community spirit.

These activities cultivated creativity and confidence, but also echoed the period’s patriarchal assumptions about which forms of programming were most appropriate for young women.

Young women at Tawonga posing, ca. 1932

Young women at Tawonga posing, ca. 1932

What Does "Tawonga" Mean?

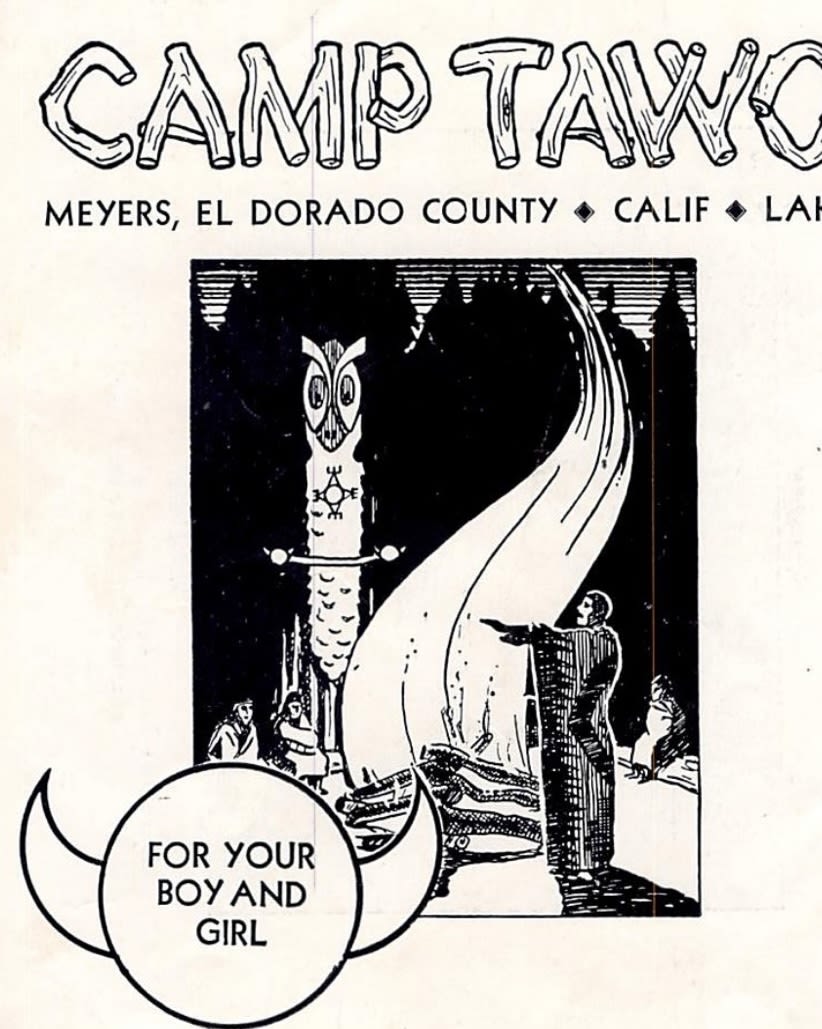

The name "Tawonga," as far as the record shows, is an invented word. There is no evidence that the YMHA camp committee (or founder Louis Blumenthal) drew it from an authentic Indigenous source.

Early generations of campers were told that the word "Tawonga" meant "I will." The assertion also showed up in at least one printed brochure (see below). But no linguistic evidence exists for the claim. It's most likely that the founders simply made up a name that sounded Native American, in keeping with a widespread practice of the period.

Promotional brochure from the 1930s

Promotional brochure from the 1930s

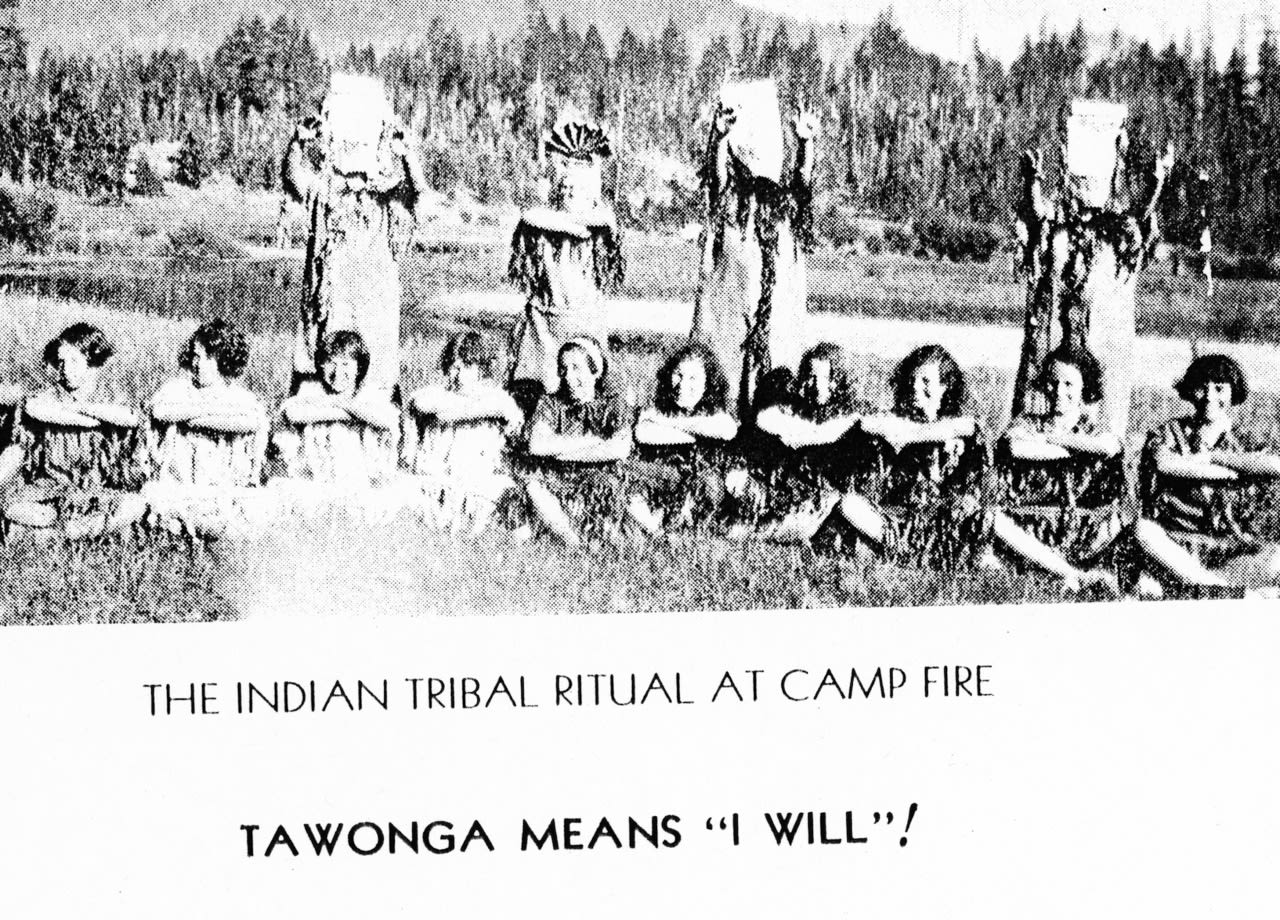

Such cultural and linguistic appropriations were far from unique. In the 1920s and 1930s, nearly every American summer camp borrowed freely from Native American imagery, themes, and names despite having no affiliation with indigenous cultures.

A group of Tawonga women in costumes intended to mimic Native American clothing, ca. 1929

A group of Tawonga women in costumes intended to mimic Native American clothing, ca. 1929

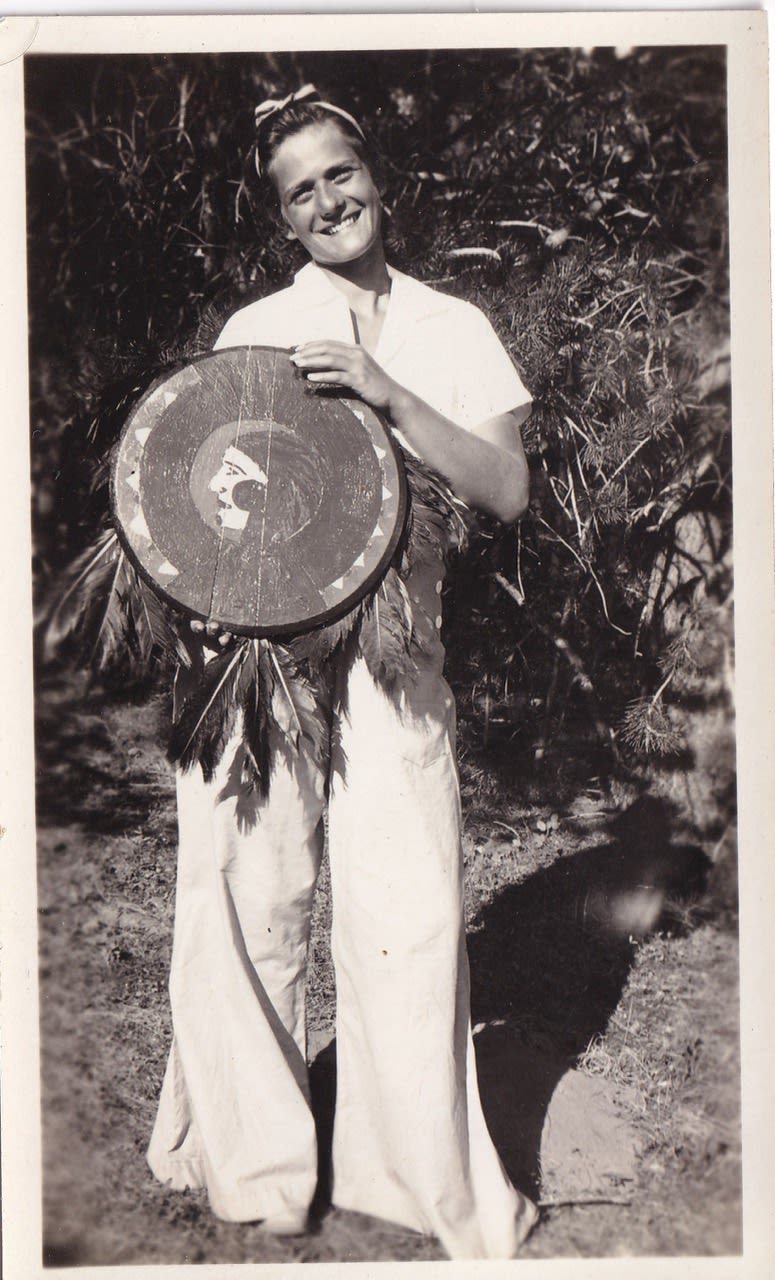

Camp Tawonga's early years followed this common practice in American camping of adopting fake Native American terms and practices. Camp groups were organized into "bands" named after different native groups or symbols; campers ran for leadership positions at the camp known as "chief brave" and "second brave;" counselors and directors led campers in invented ceremonies and rituals; and Native American-inspired images decorated camp letterhead and newsletters.

Camp Tawonga camper with imitation Native American shield, ca. 1933

Camp Tawonga camper with imitation Native American shield, ca. 1933

Image on a promotional brochure for Camp Tawonga, 1937

Image on a promotional brochure for Camp Tawonga, 1937

In later decades, Tawonga, like many camps, began to reject this pattern of appropriation. Today, Camp works in partnership with Mi-Wuk educators, honoring and respecting the original stewards of the land. Tawonga has also taken steps to recognize and highlight the archaeological sites on its property, ensuring that campers learn about the deep Indigenous history of the region. This shift reflects both a reckoning with the past and a commitment to telling a fuller, truer story of the land where generations of Tawongans have gathered.

CAMP LOCATIONS

1925–1943

Modern Tawongans have long heard that Camp Tawonga was located "near Lake Tahoe" before moving to its current location in Tuolumne County in the 1960s. This is true, but the historical record is a bit more complicated.

Because the YMHA did not own property in the Sierra Nevada in 1925, Tawonga began by renting temporary locations for the camp. As attendance increased, Camp moved several times to find locations that could serve the larger number of campers.

The following is a list of Camp's locations from its founding until 1943.

Clearlake, Calif. (1925)

In 1925, Tawonga campers gathered for the first time on a creek near the town of Clearlake. The site worked well enough for the first year, but camp leaders turned the next year to a more remote location in the Sierra.

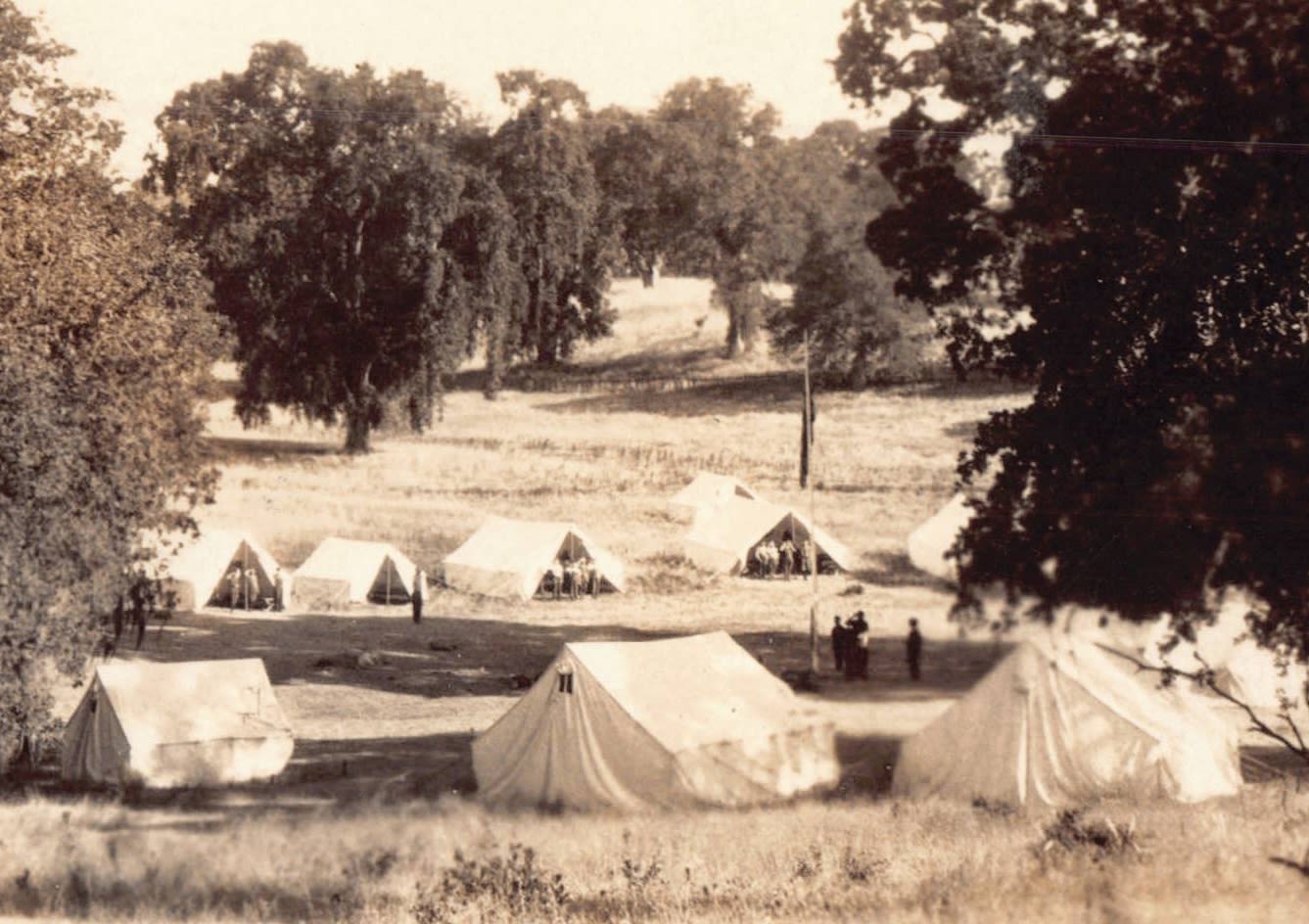

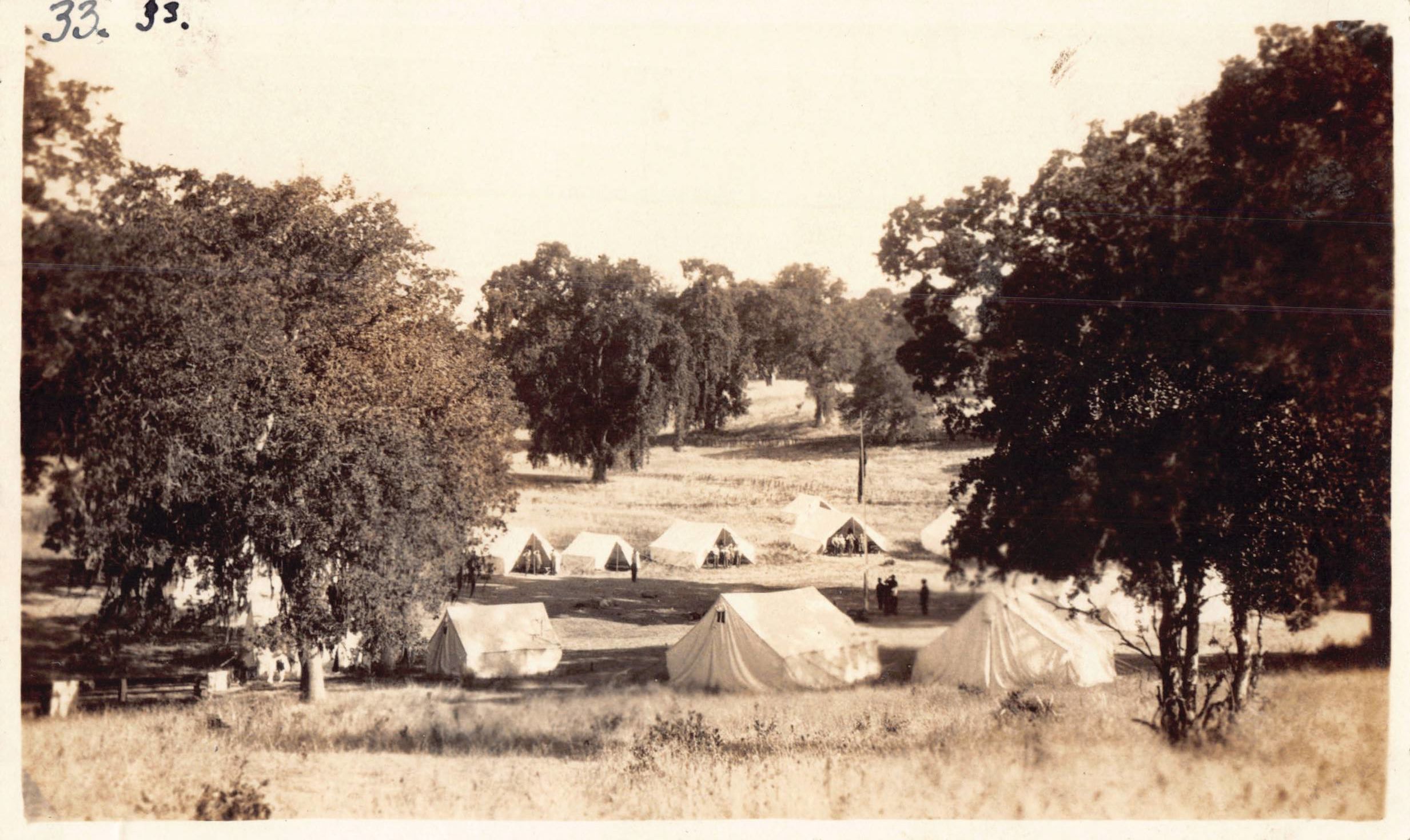

This photograph, labeled "Lakeport, 1925," is from one of Tawonga's early scrapbooks. Lakeport was a town on the other side of the lake from camp's actual location, which was close to the town of Clearlake. On close inspection, evidence in the photo suggests that the attribution of both place and date are wrong. The photo is actually from 1927 when Camp was located near Cisco, Calif.

This photograph, labeled "Lakeport, 1925," is from one of Tawonga's early scrapbooks. Lakeport was a town on the other side of the lake from camp's actual location, which was close to the town of Clearlake. On close inspection, evidence in the photo suggests that the attribution of both place and date are wrong. The photo is actually from 1927 when Camp was located near Cisco, Calif.

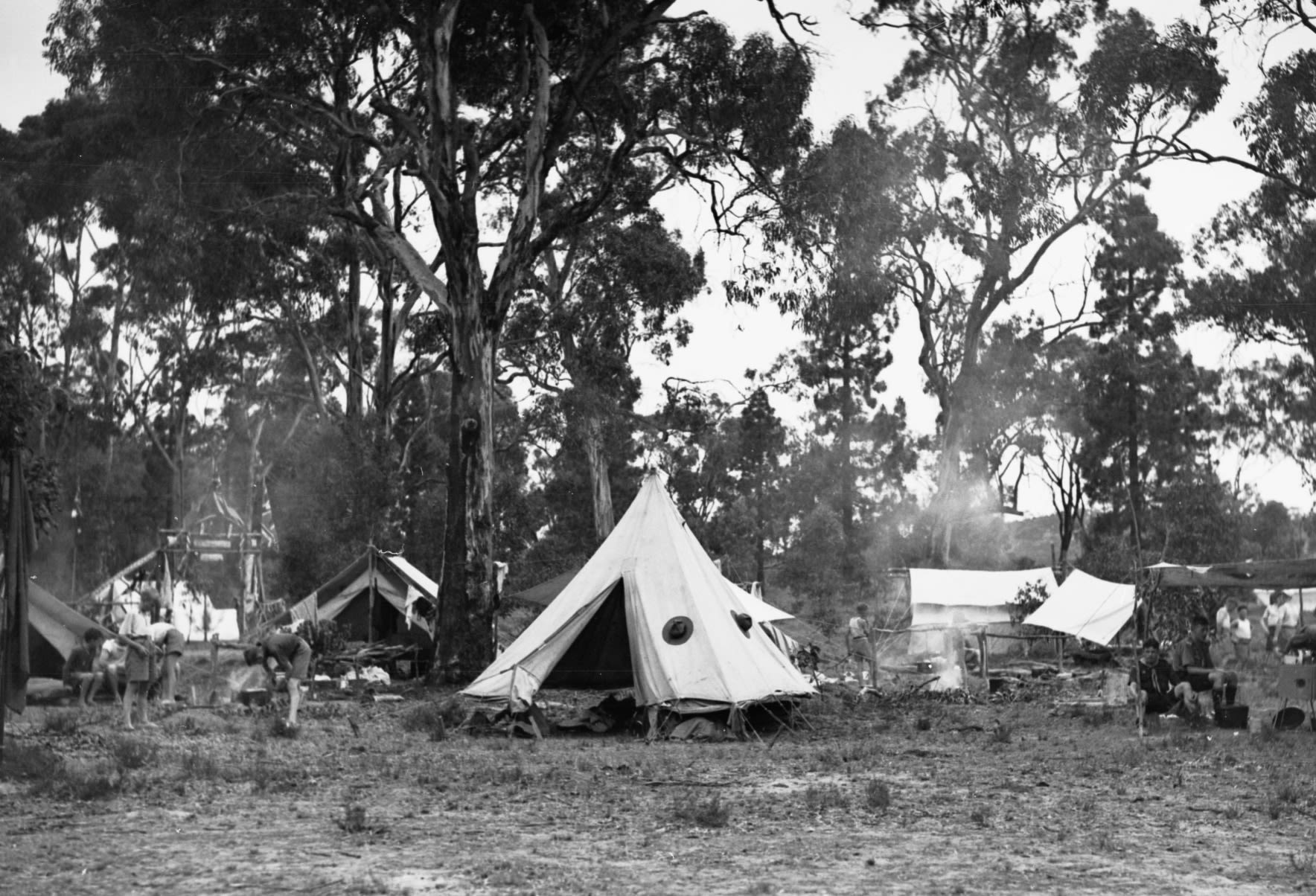

Cisco, Calif. (1926–1927)

In its second year, Camp Tawonga relocated to Cisco, a small railroad stop near the Emigrant Gap on the road to Truckee. The site sat beside a Southern Pacific train shed, built to shield tracks from snow and avalanches.

Cisco location in 1927

Cisco location in 1927

"I helped set up the camp, which was very primitive. We started from scratch. I helped dig the latrines and drove the flat-bed Model T Ford truck up to the snow sheds at Cisco to pick up supplies and mail for the camp."

The Ford truck mentioned in David Greenberg's memoir

The Ford truck mentioned in David Greenberg's memoir

Quincy, Calif. (1928–1929)

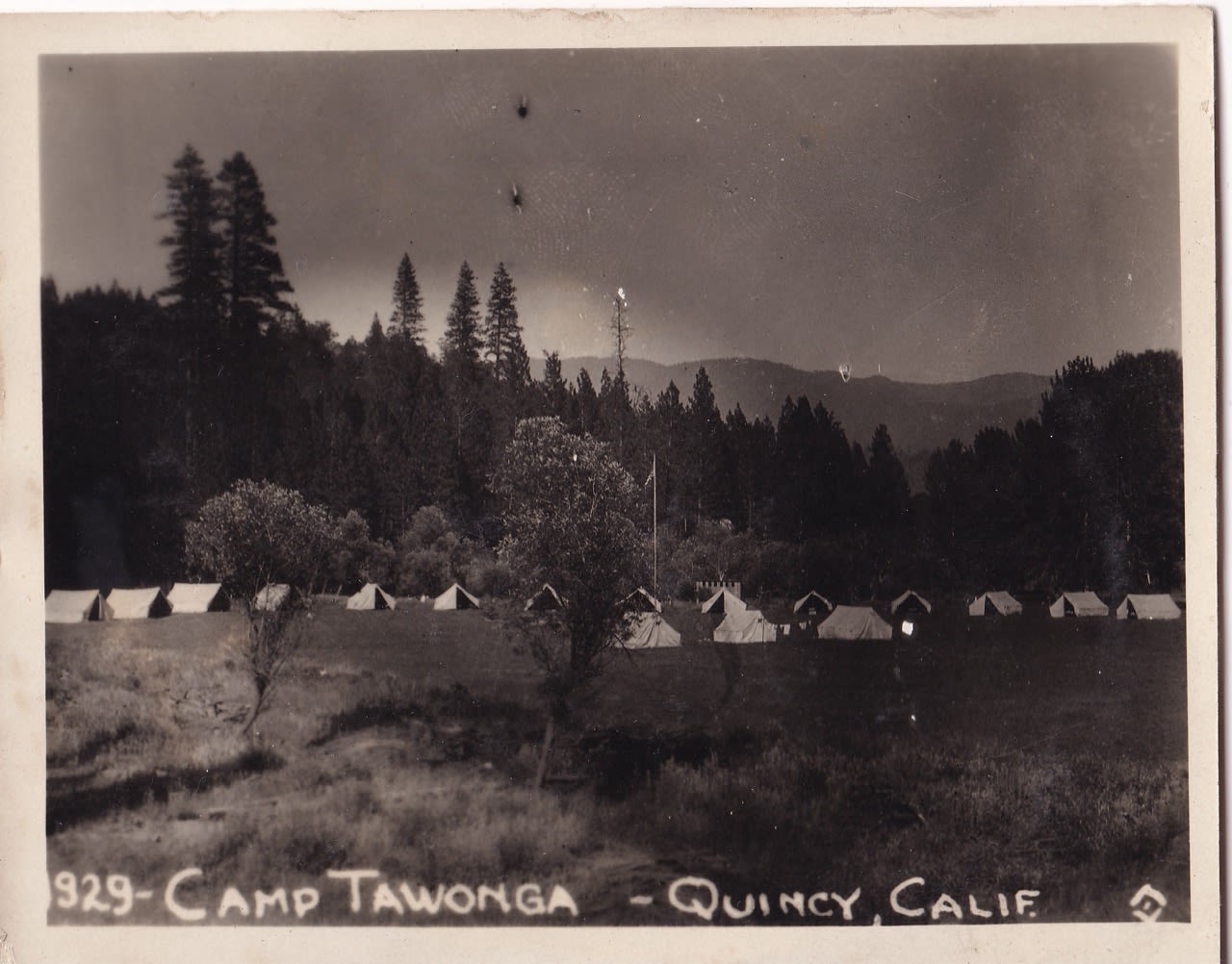

As camp attendance continued to grow with each passing year, Tawonga sought out locations that could accommodate more campers. After two years near Cisco, Tawonga moved again, this time to a location near the former gold rush town of Quincy in Plumas County.

Quincy location, 1929

Quincy location, 1929

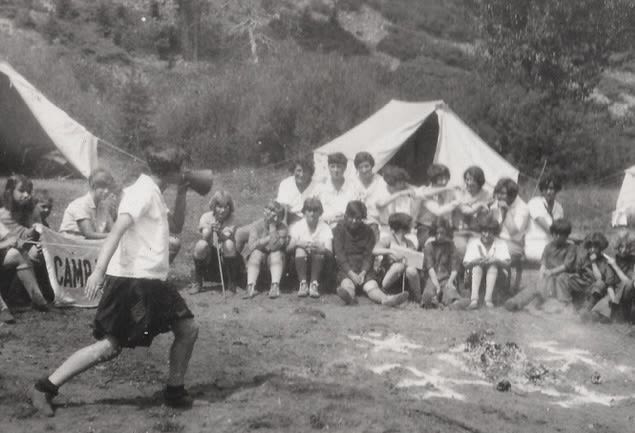

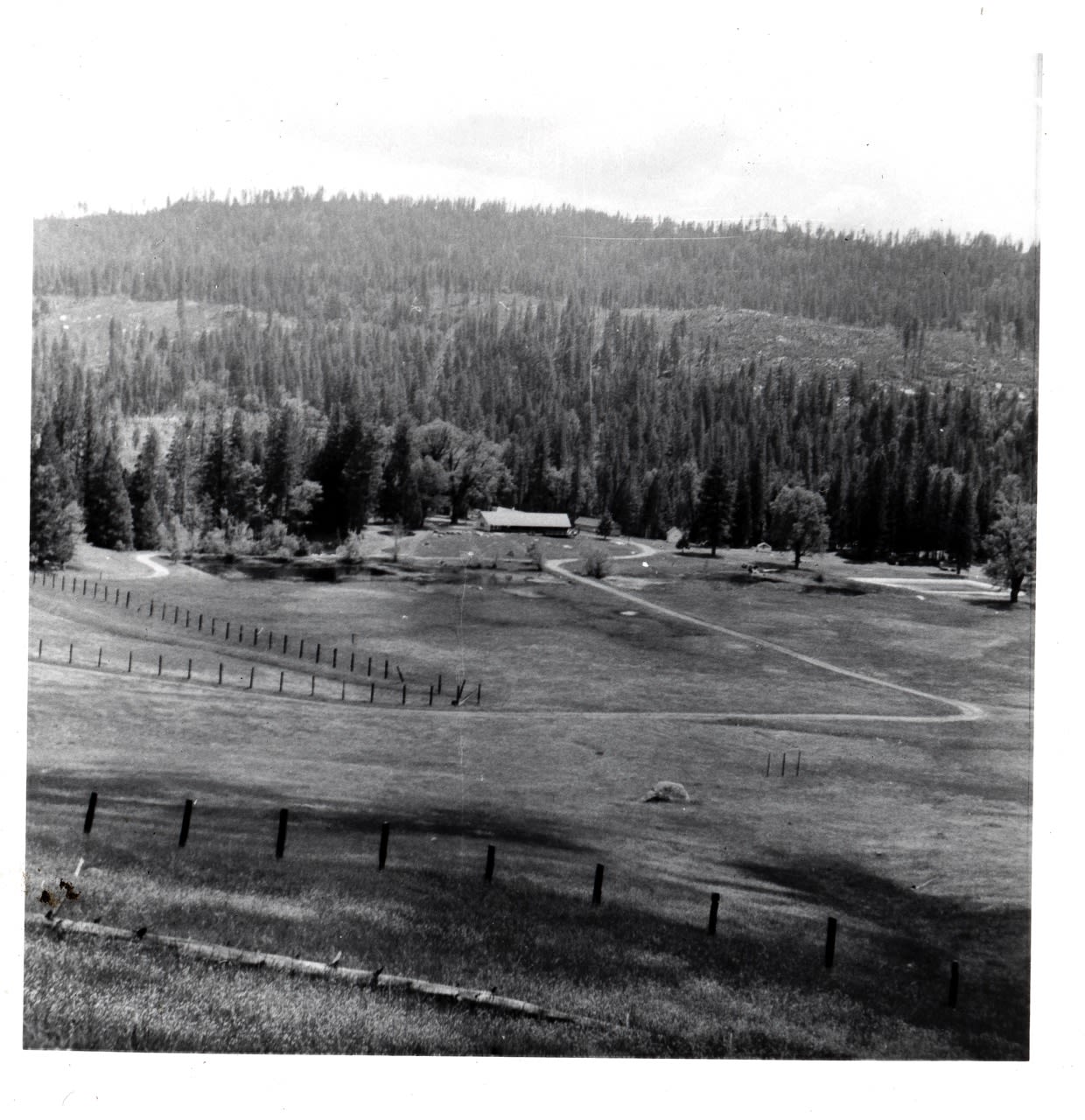

Meyers, Calif. (1930–1943)

After renting temporary locations in several different locations, Camp Tawonga eventually found a more permanent home near the shores of South Lake Tahoe. The YMHA's camp site committee found and purchased a plot of land near the town of Meyers for $3,000 in 1930 and began to raise money to build a small number of permanent buildings.

Meyers (South Lake Tahoe) location, 1930s

Meyers (South Lake Tahoe) location, 1930s

After investing funds in basic infrastructure and plumbing, Camp Tawonga gradually built a set of seasonal tent cabins to replace the much more basic tents of previous locations, an infirmary, a "wash building," latrines, and a separate mess hall for meals.

The new location's proximity to Lake Tahoe also offered campers the chance to go on regular boating expeditions on the lake.

World War II

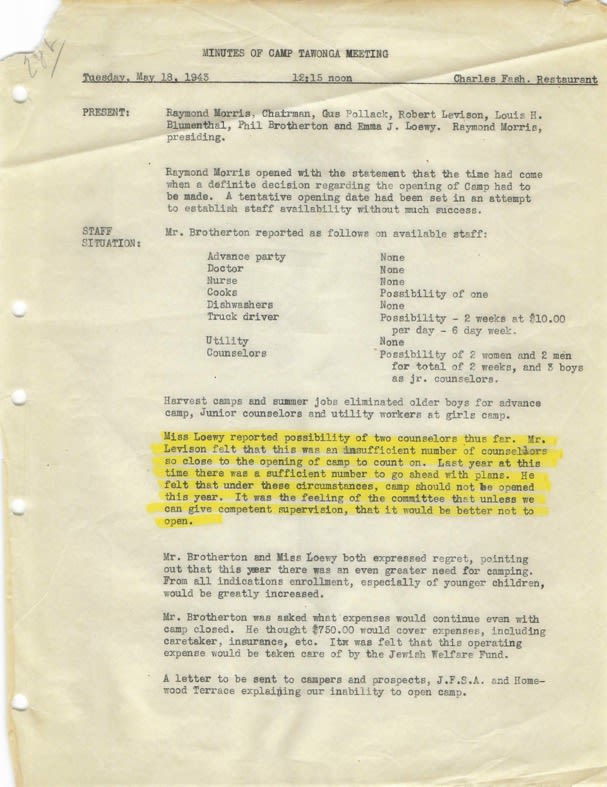

Although Tawonga successfully weathered the financial strains of the Great Depression, the restrictions of World War II proved a tougher challenge. By 1941, wartime rationing saw significant shortages in food, tents, and medical supplies.

In 1942, the camp could not hire a doctor and struggled to retain a cook.

The final blow came with the steady disappearance of counselors, as young men and women left for military service or wartime jobs. Running the summer camp came to feel like an unaffordable indulgence in a nation mobilized for war.

The staffing pressures proved insurmountable. One newspaper later reported that all but two of Tawonga’s counseling staff had departed for military service. In 1943, Tawonga's board of directors reluctantly voted to close the camp. Without income to pay off the property mortgage, they were forced to sell the Meyers site.

Hiatus

From 1944 to 1964, the Camp Tawonga committee of the United Jewish Community Center (successor to the YMHA) continued to meet annually to consider reopening.

Each year, despite strong community enthusiasm and financial pledges from alumni, the committee concluded the goal remained out of reach. The key hurdle was always the same: the lack of a permanent site.

New Beginnings

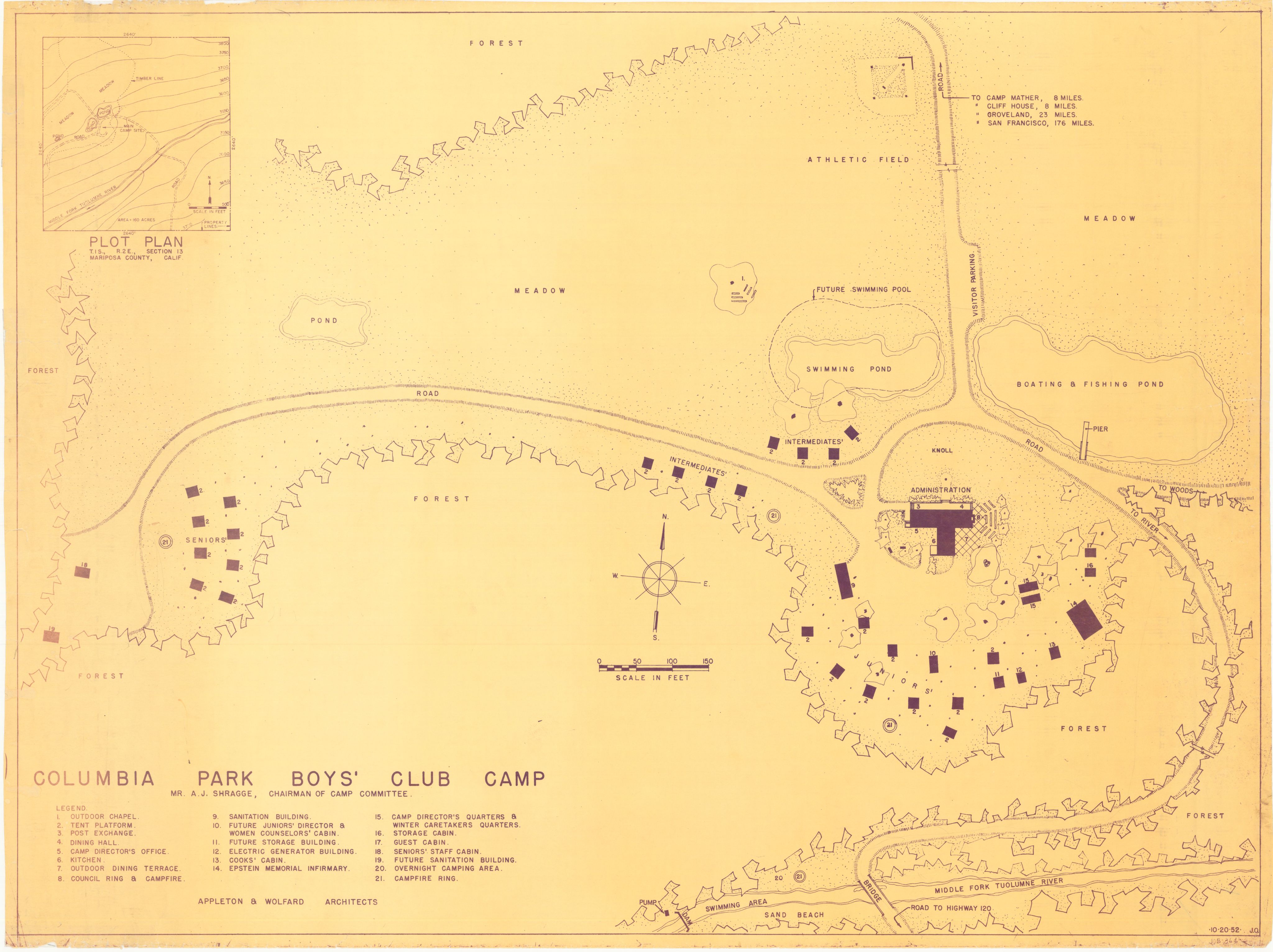

In 1965, after a long search headed by the Jewish community leader Robert E. Sinton, Camp Tawonga announced the purchase of a 160-acre property in Tuolumne County from the Columbia Park Boys' Club.

The new site came with a dining hall, tent cabins, a few simple wood cabins, a caretaker’s home, an infirmary, and a “regulation swimming pool.”

More importantly, it offered a spectacular setting of mixed conifer forests and mountain meadows, with the Middle Fork of the Tuolumne River running through it. (A Jewish Bulletin article at the time optimistically assured readers that the river would give campers “opportunities for canoeing, sailing, water skiing, water games and carnivals.”)

On June 27, 1965, Tawonga reopened its gates. That first summer in Tuolumne County, 430 boys and girls aged 8 to 16 attended camp. For the first time in Tawonga’s history, the sessions were co-ed — boys and girls camping side by side.

The Story Continues . . .

Almost Heaven:

A Visual History of 100 Years of Tawonga

We hope you've enjoyed this overview of Camp Tawonga's origins from 1925 up until 1965. We have a lot more planned in the coming months.

Future chapters will focus on a variety of topics and different aspects of Camp's history, such as:

The Dining Hall, Kitchen, and Food

Judaism and Jewish Programming

The Camper Experience

Quests, Backpacking, & Wilderness Programming

Lifelong Connections

and MORE!

Chapter 2: The Land

Coming in January 2026

An overview of our 160-acre property in Tuolumne County.

Chapter 3: Music, Songleading and Performance

Coming in early 2026

Learn more about history of music, song, and song leaders at Tawonga